Approaches to addressing gender-based violence: Lessons from the field

Gender-based Violence (GBV) is a violation of an individual’s rights, undermining their safety, security, health and dignity. GBV also has widespread ramifications for families and communities, and increases pressure on the health, social and justice systems of countries. Furthermore, when justice and social systems fail, either due to limited capacity or deeply entrenched harmful social norms, perpetrators act with impunity, perpetuating cycles of violence and preventing survivors from realising their rights. Individuals who are vulnerable to, or survivors of violence face significant challenges in fulfilling their rights to security, education, health, employment and to actively participating in their communities.

What is gender-based violence and why does it matter?

Globally, it is estimated that one in three women will experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetimes.[1] The vast majority of GBV perpetrators are men and survivors mostly women and girls. While survivors of GBV are diverse and include women, men, girls and boys, for the purpose of this paper the focus will remain on women and girls, the impact of violence on this group and lessons from Cowater’s experience addressing GBV.

By definition, GBV encompasses any act of violence perpetrated against an individual because of their sex, gender identity, sexual preference or because of “perceived adherence to socially defined norms of masculinity or femininity”.[2] In many societies around the world, there remains significant social stigma and victim-blaming related to GBV and so, many incidents go unreported. Moreover, GBV prevalence is difficult to measure due to ethical and safety issues related to collecting information from survivors who fear reprisal.

The occurrence of GBV is deeply rooted in gender inequality between men and women and exacerbated by harmful conceptions of masculinity which come with patriarchal power imbalances embedded in culture, economy and law.[3] In order to effectively reduce violence, a comprehensive approach is needed, addressing structural, economic and social inequality.

GBV affects people of diverse socio-economic backgrounds, ethnicity, culture, age, gender and location, and means that survivors seek support and services through different channels, if at all. Support services may be formal, such as health care, police and psycho-social services; or informal, through community mechanisms, familial networks or traditional leaders. Global best practice recognises three distinct areas of work for GBV prevention:

- Primary prevention – preventing the occurrence of violence against women and girls who have not experienced it and preventing new incidents against those who have;

- Secondary prevention, also known as response – preventing further violence and providing support for survivors (heath, judicial and social services); and

- Tertiary prevention, which contributes to response – providing long-term support to meet the legal, advocacy and psycho-social needs of survivors.[4]

Evidence demonstrates that the most effective approaches to reducing GBV are gender transformative. This means challenging harmful social norms and promoting the status of women more generally, not just attempting to address the attitudes and behaviours of the perpetrators and survivors directly involved.

Intersectionality

Gender inequality itself is complex, with women experiencing different challenges and obstacles as other aspects of their situation (poverty, remoteness, disability, ethnicity, etc.) interact. For example, in Cambodia, women with disabilities experience similar rates of intimate partner violence as other women, but significantly higher rates of all forms of violence from family members. A 2013 study found that they were much more likely to be insulted, belittled, intimidated, and subjected to physical and sexual violence than their peers without disabilities.[5]

The intersectionality of various factors increases women’s vulnerability to violence. It also impacts their access to information about their rights and available services, leading to marginalisation. Systems and initiatives which aim to prevent violence and/or support women survivors need to be cognisant of the intersectionality of inequality with other factors and ensure that the services they provide are inclusive and accessible for all. Cowater is working in a number of countries around the world to strengthen services for survivors of GBV, tackle inequality and enhance inclusivity.

In practice: lessons from our projects

Policy Advocacy

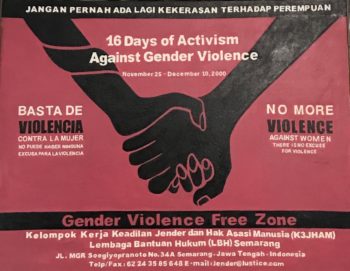

In Indonesia, on the DFAT-funded women’s empowerment program, MAMPU, significant progress has been made to influence policy change to combat violence against women (VAW). In addressing VAW, MAMPU focusses on policy advocacy and enhancing the quality and sustainability of services for women survivors of violence. To achieve this, MAMPU uses a range of complementary strategies, including engaging with strategic stakeholders such as parliament, CSOs, community and educational institutions; conducting advocacy campaigns to raise public awareness of VAW and generate political commitment for change; supporting data and evidence-based policy development; and improving service provision.

MAMPU has supported local partners to advocate for a Draft National Law on the Elimination of Sexual Violence. As a result, the Bill was officially added to the National Priority Legislative Agenda. In 2019, MAMPU and partners will advocate for Parliament to pass the Bill and support the Government to roll it out nationally.

MAMPU partners and local governments are collaborating with religious and customary organisations and media to undertake more comprehensive campaigns to address VAW and gender inequality in communities. The program is establishing community-based support for survivors of violence and empowering women through grassroots community engagement. Community-based services provide a critical first point of contact for women affected by violence, facilitating their access to community and government services.

The achievements realised on MAMPU were endorsed by the Office of Development Effectiveness during their strategic evaluation of Australia’s development assistance to end violence against women and girls. Their findings noted that there is evidence that MAMPU’s support to integrated service centres has contributed to formal services being more accessible and more survivor-centred. Furthermore, in recognition that most women do not access formal services, the review recommended continued support for women’s grassroots community groups, as a first line of support for women and girls experiencing violence.[6]

Enhanced service delivery

Inclusive and quality delivery of services to survivors is vital to minimising long-term, devastating consequences to their physical and mental health. Services must be accessible, safe, non-judgemental and effectively coordinated, linking health care with psycho-social and justice services.

In Cambodia, Cowater is implementing the Australia-Cambodia Cooperation for Equitable Sustainable Services (ACCESS), which is improving the quality and sustainability of services for women affected by GBV and persons with disabilities. Individual women and girl survivors of violence have unique needs, defined by the type of violence experienced, the survivor’s socio-economic situation and other contributing factors such as poverty, disability and marginalisation.[7] Survivors require access to health care, justice and essential social services.

Applying a human rights-based approach, the program is supporting enhanced coordination and improved capacity of key actors in the system, which is leading to a higher quality of service delivery overall. Importantly, ACCESS is integrating intersectionality considerations into service delivery to ensure that women with disabilities, poor women, women in remote locations or from ethnic minority groups have equal access to essential primary, secondary and tertiary prevention services.

Educating people on their rights

In Malawi, where two in five women experience physical or sexual violence[8], educating women and men, girls and boys on their rights and integrating rights-based approaches into service delivery is critical to reducing violence and its harmful health impacts. The Integrated Pathways for Improving Maternal, Newborn and Child Health program (InPATH) funded by Global Affairs Canada is mainstreaming GBV awareness into Maternal, Newborn and Child Health services. By improving reporting and referral systems in health service delivery, safeguards to protect women and girls from violence are enhanced and survivors are enabled to realise their rights. The project is training Community Midwife Assistants to recognise signs of GBV as a first point of contact within communities, provide counselling to survivors, refer survivors to other necessary services and educate communities on the impacts of GBV. The program leverages existing community and district structures, including local and traditional leaders, to educate people of their rights and address gender inequality more broadly. To contribute to this aim, InPATH is also rolling out training on Sexual, Reproductive Health and Rights, including GBV to the district-level Gender Technical Working Groups which coalesce representatives from district government and services including health facilities, police and social welfare to collectively address issues relating to gender equality in their districts.

Community engagement

Community engagement can be a force for social and normative change when accompanied by institutional and  regulatory approaches to preventing and reducing GBV. As demonstrated above, communities have been critical in educating women and men on their rights and linking them with essential services. On the Women Defining Peace in Sri Lanka project (WDP), Cowater found that GBV is most effectively addressed by engaging a diverse range of actors, including media and local media personalities, rather than focussing exclusively on women’s organisations. Another key lesson from WDP, is that the most impactful solutions for addressing GBV were those developed and driven by the community, rather than centrally-designed and imposed. In evaluating another Canadian-funded community engagement program in Sri Lanka, called the Local Initiatives for Tomorrow (LIFT2) project, Cowater found that the project was able to bring the discussion of the otherwise-sensitive issue of GBV to the fore in communities by leveraging existing community fora. Through such fora the project trained members to identify signs of violence and act as a first point of contact for women, referring them on to the formal services they require.

regulatory approaches to preventing and reducing GBV. As demonstrated above, communities have been critical in educating women and men on their rights and linking them with essential services. On the Women Defining Peace in Sri Lanka project (WDP), Cowater found that GBV is most effectively addressed by engaging a diverse range of actors, including media and local media personalities, rather than focussing exclusively on women’s organisations. Another key lesson from WDP, is that the most impactful solutions for addressing GBV were those developed and driven by the community, rather than centrally-designed and imposed. In evaluating another Canadian-funded community engagement program in Sri Lanka, called the Local Initiatives for Tomorrow (LIFT2) project, Cowater found that the project was able to bring the discussion of the otherwise-sensitive issue of GBV to the fore in communities by leveraging existing community fora. Through such fora the project trained members to identify signs of violence and act as a first point of contact for women, referring them on to the formal services they require.

*****

Drawing from our experience working on GBV around the world and global evidence, preventing and reducing GBV requires a multi-faceted, multi-actor approach. We must recognise that GBV disrupts social cohesion in communities and undermines development, and that it is driven by entrenched gender inequality. Quality, inclusive sexual and reproductive health services are lifesaving for those affected by GBV but are also critical to addressing stigma and harmful social norms which perpetuate such violence.

Cowater’s experience demonstrates that any intervention or system designed to prevent or address GBV must be gender-responsive and must include all services which are central (health, psycho-social, judicial) and peripheral (finance, education, employment) to supporting survivors to realise their rights and empowering them as individuals. Effectively addressing GBV requires a dual approach of changing social norms and behaviours, and building gender-responsive institutions, particularly justice systems, which support survivors and end impunity for perpetrators.

[1] UNFPA. 2018. https://www.unfpa.org/gender-based-violence.

[2] USAID. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2155/GBV_Factsheet.pdf.

[3] Minerson, T., Carolo H., Dinner, T. and Jones, C. 2011. Issue Brief: Engaging Men and Boys to Reduce and Prevent Gender-Based Violence. Status of Women. Canada.

[4] PSI, 2016, “Gender-Based Violence: A Review of the Evidence”, Evidence Series. Population Services International.

[5] Astbury, J. & Walji, F. (2013). Triple Jeopardy: Gender-based violence and human rights violations experienced by women with disabilities in Cambodia. Canberra: AusAID.

[6] ODE strategic evaluation of Australia’s development assistance to EVAWG-Indonesia Summary Note, October 2018.

[7] MoWA (2011). One-Stop Service Center Feasibility Study. Phnom Penh. MoWA.

[8] UNWomen, 2016, Global Database on Violence Against Women: Malawi, http://evaw-global-database.unwomen.org/en/countries/africa/malawi

Related Content

ProNurse Project celebrates International Women’s Day 2024

This year’s International Women’s Day theme was “Invest in Women: Accelerate Progress”. To celebrate and raise awareness of the role of women in the nursing sector of Bangladesh, ProNurse Project […]

Integration of Gender Equality and Social Inclusion in Water Utilities in Indonesia

Since mid-2020, Australia has supported the Performance Based Grants (PBG) scheme for water utilities in Indonesia through the Indonesia Australia Partnership for Infrastructure (KIAT). On 15 December 2023, Cowater International, […]